Optic neuritis is an inflammation of the optical nerve. This inflammation may be located at the nerve’s front side (papillitis) or at the rear side of it (retrobulbar optic neuritis). This is the optic nerve disease that most usually causes a sudden vision loss in young patients.

The optic nerve is the structure that brings information from each of the eyes (which are the ones who receive the light from objects and transform it into nerve impulses) to the brain (that processes this information and interprets it as images; this means, conversely to what is usually thought, that we actually see with our brain, not our eyes). We could compare it to the USB wire that sends the information from a digital camera (which would be the equivalent for the eye) to a computer (which would be the brain):

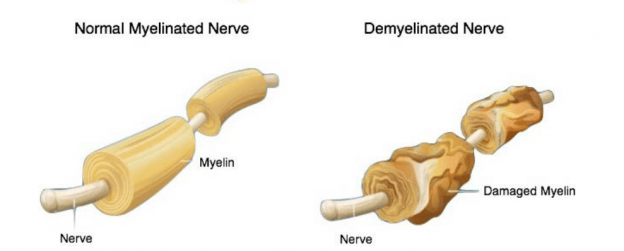

We currently don’t know exactly what are the causes of this disease. In its more common form (demyelinating optic neuritis), the layer surrounding neurons forming the optical nerve (myelin sheath) is attacked by the patient’s own immune system (autoimmune disease). Our immune system, which is usually in charge of defending ourselves from infections, mistakenly thinks the myelin sheath from our optic nerve is a foreign element that must be attacked.

It is likely that, in order for an optic neuritis episode to occur, several factors have combined. An infection (possibly a virus) that may have occurred years or even decades ago, may have triggered a particular alteration in our immune system.

This optic nerve inflammation may occur in isolation, without any more general disease associated. In such case, we say that neuritis is idiopathic, or with an unknown cause. It can also be part of a disease that may have caused inflammation in other body parts (examples: multiple sclerosis, optic neuromyelitis, sarcoidosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Wegener’s granulomatosis, Behçet disease, Lyme disease, tuberculosis, Whipple disease, etc.).

Since the myelin sheath of the optic nerve would be tantamount to insulating material that wires have in order for electricity to travel faster, if such insulating material is damaged, the signal sent by the optic nerve from the eye to the brain will travel slower and with less resolution (as it would happen with a “stripped” wire).

Therefore, the most common symptom is vision loss: you can experiment blur vision, darkened vision (as if there was less light or brightness), a part of the vision can seem to be missing (at the center or from the sides) or a permanent black spot can be seen in the visual field. This vision loss usually occurs rapidly and does not improve with any corrective eyeglasses.

Other frequent symptoms are pain in the eye or behind it, especially when making eye movements, colour vision dimming (many patients describe it as colours being less vibrant), and flashes or flashing lights (photopsias). Some patients experience blurred or darkened vision for some minutes (and up to an hour) when it’s hot, or after practising some sport or showering with hot water (this is known as Uhthoff’s phenomenon).

Since the eye can have a normal appearance, it may be hard to diagnose. Therefore, it is essential to take into account not only the current patient symptoms and its progression since the beginning, but also all previous disease or other data from clinical records (diets, consumption of toxic substances, pets…) that may be relevant in order to shed light on the current problem.

Then, a comprehensive and detailed neuro-ophthalmological examination will be performed, and using all the compiled data, the ophthalmologist will decide which additional examinations are required in order to complete the study. Usually, these tests will include both ophthalmology tests (campimetry, optical coherence tomography, etc.), and non-ophthalmological tests (cranial ultrasound and, depending on the case, blood tests, chest x-rays, etc.).

As we’ve mentioned before, the eye appearance may be normal (in most cases), or some liquid may be seen at the back of the eye (in the optic nerve head). This may be also due to other disorders different from inflammation (optic nerve infarction, high intra-cranial pressure, genetic disorders…).

The optic neuritis diagnosis is, initially, a suspected diagnosis, which will be confirmed or rule out depending on the evolution of symptoms and the findings of different examinations. If the progression does not follow what we call the typical optic neuritis pathway, the studies will focus on other suspected diseases (by means of genetic analysis, lumbar puncture for the study of cerebrospinal fluid, etc.).

Luckily, most patients’ vision substantially improve, whether a treatment is or isn’t provided. In typical optic neuritis cases, the treatment with corticosteroids has been proven to speed up the recovery, but the final vision will be the same as if no corticosteroids were used. This means, corticosteroids help the nerve de-inflame faster, but vision will get to the same point with or without them. Atypical optic neuritis cases may require treatment with high-dose corticosteroids, antibiotics or other drugs, depending on each specific case.

In children, optic neuritis usually affects both eyes, while in adults usually only one eye is affected. Moreover, children with optic neuritis may suffer from fever, flu-like symptoms, and they are likely to have recently suffered a disease or been vaccinated before the onset of the symptoms, which is not likely in adults. Furthermore, adults suffering from optic neuritis are in higher risk of suffering multiple sclerosis, a risk which is far lower in children.

Contact us or request an appointment with our medical team.